Among the most persistent myths surrounding "Another World" is that its creator, Irna Phillips, was heartbroken when CBS had no room in its daytime schedule and the show went to NBC. However, when Lynn Liccardo, author of the Kindle Single, "as the world stopped turning...," posed the question to former Procter & Gamble Productions executive, Ed Trach, he told a very different story.

According to Trach, sometime in 1963, NBC approached PGP about Irna Phillips creating a new serial for them. AW was never offered to CBS, a fact confirmed by Fred Silverman, then head of CBS Daytime. Trach went on to reiterate that PGP had no interest in placing another serial with CBS. Silverman suggested that by expanding their daytime footprint beyond CBS, PGP hoped to improve their bargaining position.

It was the success of "As the World Turns" that made NBC so eager to sign Phillips. According to Trach, ATWT was drawing higher ratings than all but three of the shows in NBC's primetime lineup at the time. But Phillips' concerns about placing a new serial on NBC were well-founded. Prior to AW's debut in May 1964, there had been 19 serials on NBC (beginning in 1949, with Phillips' "These Are My Children"). Only seven lasted longer than a year, including "The Doctors," which debuted in in 1963 as a daily anthology. When that format proved financially untenable, the show moved to weekly arcs. In March 1964, two months before AW's premiere, "The Doctors" became a daily serial.

In a press interview prior to the show's debut, Irna revealed she took the title for "Another World" from two lines by John Keats: "We live not in this world alone, but in a thousand worlds." "What I want to say is that none of us can face reality 24 hours a day. We must have private 'worlds'-made up of our own dreams and pleasures and emotions into which to retreat. Otherwise, it would be simply too much! But always in terms of the family. In every story I have ever written, the home and family have been solidified, not attacked."

The actual and full quote shows it not to be a yearning for different types of experiences, but instead a treatise on solitude and finding beauty in life's minutia: "I hope I shall never marry. Though the most beautiful Creature were waiting for me at the end of a Journey or a Walk; though the Carpet were of Silk, the Curtains of the morning Clouds; the chairs and Sofa stuffed with Cygnet's down; the food Manna, the Wine beyond Claret, the Window opening on Winander mere, I should not feel - or rather my Happiness would not be so fine, as my Solitude is sublime. Then instead of what I have described, there is a sublimity to welcome me home - The roaring of the wind is my wife and the Stars through the window pane are my Children. The mighty abstract Idea I have of Beauty in all things stifles the more divided and minute domestic happiness - an amiable wife and sweet Children I contemplate as a part of that Beauty, but I must have a thousand of those beautiful particles to fill up my heart. I feel more and more every day, as my imagination strengthens, that I do not live in this world alone but in a thousand worlds" - John Keats, The Letters of John Keats, 1814-1818, Volume One.

In the first page of the show bible, the new show is placed "not too far" from ATWT's Oakdale and Chris Hughes is specifically referenced and tied to the Matthews family - he even attended the funeral of Will Matthews prior to the debut episode. Beyond the bible, the episodes broadcast were less interested in that connection. Oakdale was mentioned only twice (May 8 and June 11) in an almost disparaging way. "They know know people there but not friends," commented Alice to Granny. It wouldn't be until six months later that an ATWT actor crossed over and joined the cast as the same character - Geoffrey Lumb as attorney Mitchell Dru.

Without any crossovers between the shows in AW's first six months, AW could not be considered a spinoff or sister show of ATWT. There are no references of a connection to Oakdale in the very rough first draft of Phillips' unfinished memoir, "All My Worlds."

It's more likely that the bible made references to the top-rated ATWT as a way of reminding her audience of her successful track record, as well as a way to bring her AW characters into sharper focus.

What Irna Phillips did understand was that ATWT viewers were the natural audience for AW. On the final page of AMW, she shared her clever -- some might say brilliant -- idea to reach them. In the fall of 1963, ATWT celebrated Grandpa Hughes' 70th birthday. The 150,000-200,000 viewers who included a return address on the cards they sent received a note a few weeks before the AW premiere, thanking them and letting them know about a new show on NBC. The gist of the promotion: "if you like the Hughes family, we think you'll also like the Matthews."

Bill Bell began writing for "Guiding Light" in 1956, moving to ATWT in 1958. He described co-creating AW with Phillips as, "a whole new learning experience," later admitting that launching a series with a funeral was too depressing. However, in AMW, Phillips seems to disparage Bell's involvement: "If I were to be asked why I gave Mr. Bell and a few other people who had absolutely nothing to do with the writing of scripts, part ownership of this program, I'm afraid the answer is almost too simple. As I've said before, I'm essentially a teacher and a teacher's function is not only to impart whatever knowledge she can to her students, but to give them whatever she feels will be a help to ensure, if she can, their future."

However, Liccardo notes that Phillips was writing AMW at the end of her life, after a decade filled with professional failure and personal loss, including Bill Bell's departure when he took over as Days of Our Lives headwriter after Ted Corday's death. Liccardo points out while Phillips is careful to note Bell's kindness to her children, just below the surface her sense of betrayal -- and anger -- is palpable.

In her research, Professor Elana Levine, author of the forthcoming "Her Stories: Daytime Soap Opera and US Television History," found the original documents that provided details on the shared ownership of "Another World." The show s official and legal agreement (dated 5/4/64) established that P&G Productions and Young & Rubicam would acquire rights to AW from Phillips, Bill Bell (the show's co-writer), Rose Cooperman (Phillips' private secretary), and Arno Phillips (Phillips' brother).

The agreement was for 268 consecutive weeks, but could be terminated at the end of shorter cycles within. Owners were to be paid $1,000/week royalties for the term of the agreement. A purchase price of $500,000 was set. Broadcast rights were for the US, Puerto Rico, and Canada. Phillips and her co-owners transferred their rights, title, and interest in "Another World" for $500,000 in a purchase agreement dated 4/10/67, to be paid in 11 annual installments between 1967 and 1977. Distribution: Irna Phillips 39%. William Bell 31%. Rose Cooperman 5%. Arno Phillips 25%.

According to Levine, what's significant here is that P&G did not own AW until 1967. Phillips and her partners did and they licensed it to P&G and their ad agency, Young & Rubicam, during that time. This may be the first time a creator owned their own soap, even as it was temporary and in P&G's hands from the beginning.

Towards the end of the AMW manuscript, Phillips discusses how she came to create "Another World." She says that the idea of writing a new and different kind of serial came to her when she found herself wondering about the possibility of using her own life as the basis of a serial, focusing it on an "illegitimate" young woman who'd been raised in an orphanage and who "lived most of her life in a world she created for herself." She'd always claimed to be a lonely child growing up, and would make up long and involved stories for her dolls to live out. She elaborated on the idea of alternate personal worlds to the psychiatrist she had been seeing for depression following a heart attack several years earlier

"This is the first time that I told the doctor that I had come to believe and that I still believe, always will, that to face reality day in and day out without escape, without surcease, would be impossible for any of us. I was sure we couldn't with any degree of sanity, live only in a world of reality. In a way the doctor agreed with me, in another way he didn't. It was difficult to accept that we have to learn to cope with a certain amount of reality. I knew he was right. I asked him if it was advisable that I start on a new serial. "Isn t that what you ve been doing?" "I have a title, it s based on what we ve been talking about." "Oh, a bit of fantasizing!" "Another World was my answer. This then became the germ of the next serial I created and presented to Procter & Gamble.

"It would be difficult for me to say how long "Another World" seemed to be lying dormant before I even recognized it as an idea and began to think of it as a potential for a continuing drama. Bill Bell was working with me on "As the World Turns," and I have always had the habit of discussing my ideas with whomever I might be working. All told, Bill and I spent two Saturdays talking about Another World after which I proceeded to write the most informal, loosely put together presentation."

Phillips' original title for "As the World Turns" was "As the Earth Turns," but it was changed because there was a novel with the title "As the Earth Turns." The list of alternate titles came from copywriters from the Ivory Snow Group. Phillips went on to embrace the word "world," imparting it to three of her following shows ("Another World," "A Private World," and "A World Apart") as well as the title of her memoirs, "All My Worlds."

One day in the living room of Phillips' home, accompanied by her secretary Rose Cooperman and her writing assistant Bill Bell, she was joined by Bob Short (head of daytime television for P&G), Edward Trach (an ATWT supervisor), and a representative of the Young & Rubicam agency. (In those days, ad agencies often handled the production of the daytime dramas.) Copies of the presentation were on the card table along with sample scripts. Years ago, Phillips had spent $5,000 of her own money to finance the "Guiding Light" pilot and had never been reimbursed. Tonight, she informed her guests that they could see neither presentations nor scripts unless they optioned the program for $5,000.

"It wasn't the best presentation I had ever written or as good as others I would write in the future, but as I was told only matter of months ago, "We bought 'Another World' on your track record, not by what we read in the presentation.'"

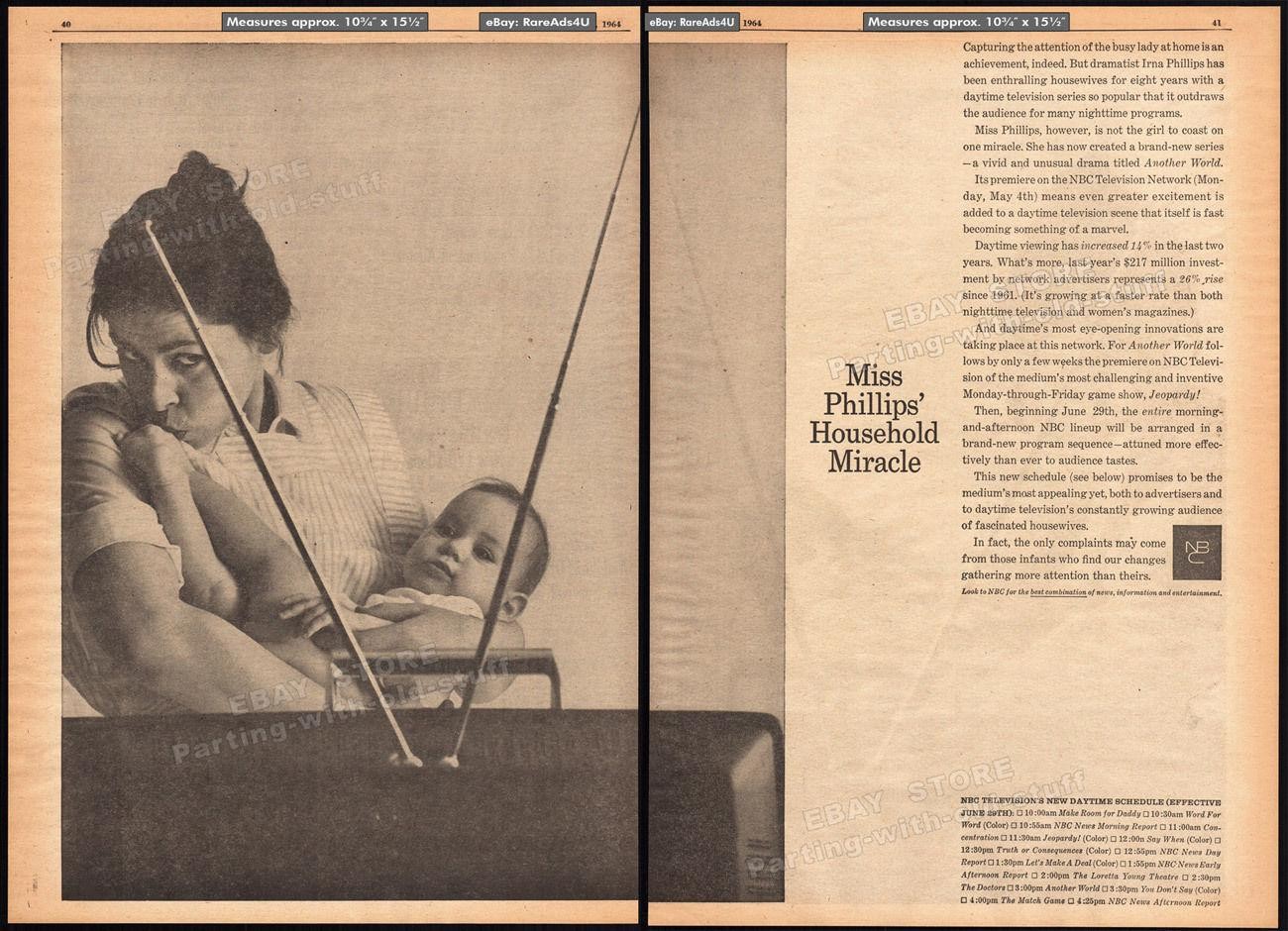

At first glance, the AW's bible reads like an overtly feminist serial. There are explicit references to "The Feminine Mystique," published in February 1963 by Betty Friedan. It explored the frustration felt by many American women in the late 1950s and early 1960s who felt locked in to the traditional gender roles of wife and mother. This sentiment is mirrored in the bible: "there's a question in the minds of many today whether the woman at home is really a fulfilled woman; or is she, as she s been pictured from time to time, forever seeking in one way or another seeking to escape the boredom of being only a wife and mother." This is well represented in the character of Janet Matthews, a single career woman in her 30s. From the influences of her own early life, Phillips remained committed to traditional values and gender roles. As her bible goes on to say: "the business world in itself cannot bring a woman happiness and fulfillment."

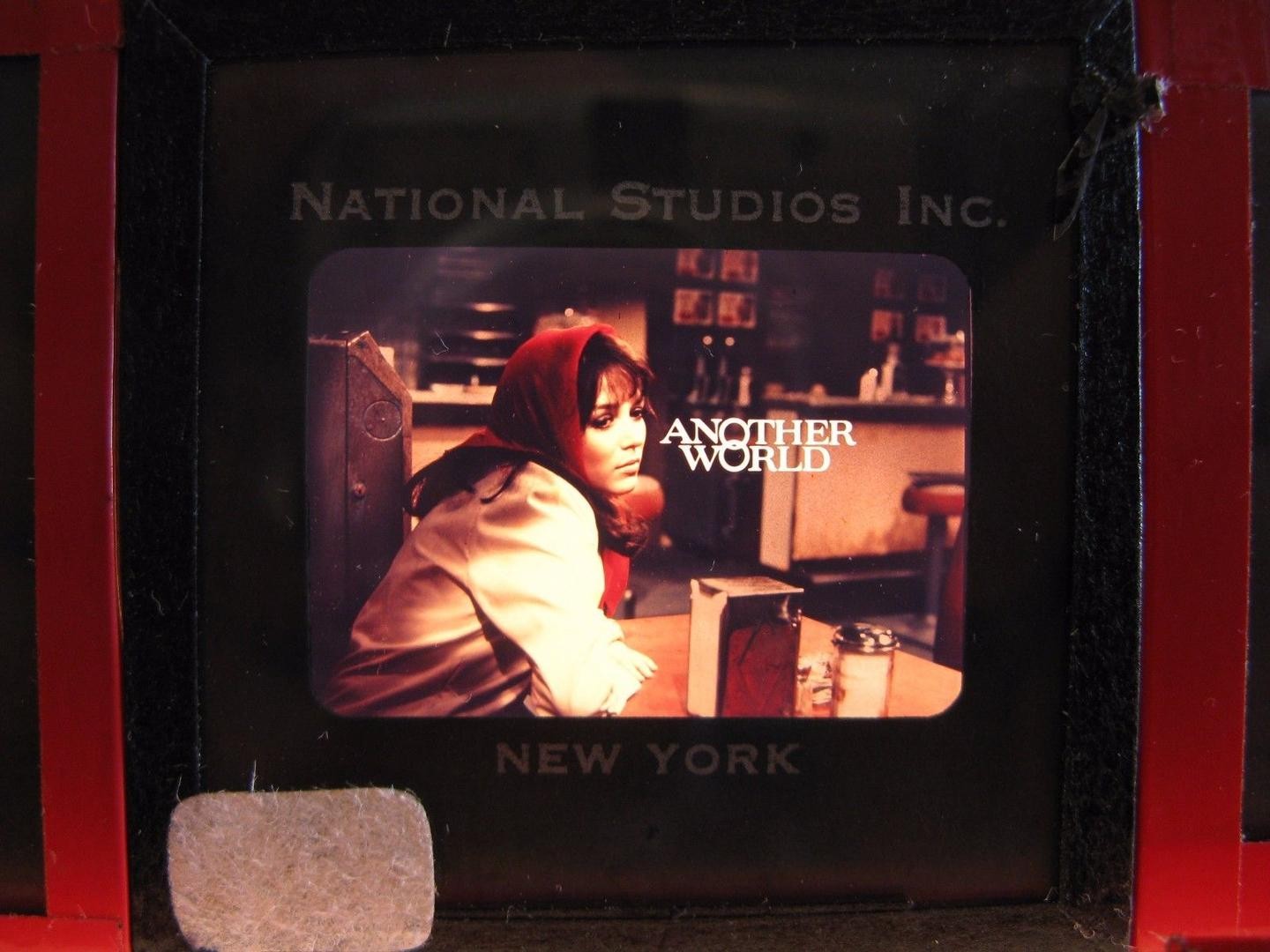

But that is not the story that played out. And the storyline that did dominate the show's first year -- the relationship between Pat Matthews and Tom Baxter, which led to Pat's abortion and sterility, then ended with her killing Tom -- is nowhere to be found the AW bible. While it's not surprising that in 1963, ten years before Roe-v-Wade legalized abortion, Phillips would have anticipated that NBC would be reluctant to tell such a controversial story, according to Liccardo, "Concealing the true thrust of a story was vintage Irna, who often treated "the suits" like mushrooms: "Keep them in the dark and periodically give them a load of manure." Actor Don Hastings, who wrote for ATWT in the early 1970s, told Soap Opera Weekly in 2007, that after the suits left, Irna would say, "now here's the story we're really going to write."

This was particularly true when those stories ran counter to the social mores of the times, like abortion -- and adultery. Eight years earlier, in the ATWT bible, there's little to suggest that an Edith/Jim/Claire triangle would dominate the show's first year. By the time PGP figured out Irna's end game: Jim and Claire, who are both equally unhappy in their marriage, divorce, allowing Jim and Edith to marry -- no "heavy" for viewers to hate; no bad guy to punish -- there was no turning back. While this storyline forced viewers, according to the late critic, Robert La Guardia, "to grieve over the heartbreak of the human condition, rather than hang on to a fixed value judgement," PGP knew that with housewives as their target audience, there could be no happy ending for the adulterers, and so Jim was killed off.

While the AW bible may have revealed nothing about Pat Matthew's pregnancy and abortion, according to Levine, as the story unfolded, NBC censors requested a number of script changes. Some were to insure medical accuracy: making clear that the cause of Pat's sterility was the infection that resulted from the abortion, not the abortion itself. Others addressed Pat's level of responsibility for the situation, with one NBC censor warning against her being portrayed as "totally innocent or blameless." While this placed responsibility on Pat for her sexual behavior, not the unjust societal expectations of young women, Levine points out, "it also attributed to her some agency, even sexual agency 'good' young women who got themselves in such situations were not mere victims of duplicitous men."

Levine goes on to say that while these changes were likely made to provide NBC cover from being seen as endorsing immoral or illegal behavior, "they also resulted in greater ambiguity about the causes of Pat s troubles did she make bad choices or was her situation an impossible one to navigate? If the latter, what made it so untenable? The openness of soap storytelling invited such questions."

What these two storylines share is their connection to the painful and far-reaching loss Irna Phillips experienced in Dayton, Ohio in the late 1920s. In AMW, she tells of meeting a British doctor, eight years older, "not handsome, but charming and intelligent," and immediately deciding that, "he was the man I was going to marry." But when she becomes pregnant and he denies paternity, Phillips turns to her good friend, attorney, Ralph Skilken, who helps her take the doctor to court and win a $500 judgement. Back in her hometown of Chicago, Phillips describes going into premature labor, with a placenta previa, and delivering a stillborn daughter. Efforts to stop the bleeding leave her unable to bear children.

Painful as her sterility must have been, Liccardo believes that the loss that haunted Phillips for the rest of her life, the loss she would try to correct through Edith/Jim/Claire on ATWT and Pat/Tom/John on AW was her relationship with Skilken. After she returned to Dayton, their friendship deepened. While Phillips never acknowledged that the relationship was sexual, she does say, "If memory serves me correctly, I believe I might have fallen in love with him," and "Ralph's friendship and companionship did much to help restore confidence in myself as a woman," Skilken, however, told her that "if he couldn't have children of his own, he would not have any."

Phillips returned to Chicago, and in 1930 began writing the first radio serial, "Painted Dreams" for WGN radio. Skilken remained in Dayton and went on to have a life that very much resembled that of Chris and Nancy Hughes in Oakdale: successful attorney; stay-at-home mom; three children. In AMW, Phillips acknowledged that while in the past she had fictionalized aspects of her life, in ATWT, she was fantasizing as well as fictionalizing, going on to say, "For me the Hughes family represented what I imagined and believed the traditional family was at that time," the traditional family Phillips was never able to provide for herself and her two adopted children, Tom and Kathy.

While Phillips explicitly acknowledges that she's living out one aspect of her fantasy through the Hugheses, what Liccardo believes is far more revealing is what Irna doesn't say: that with Edith Hughes as her surrogate, and Jim and Claire Lowell standing in for Ralph Skilken and his wife, she would vicariously live out her fantasy of a life with Ralph Skilken. But PGP refused to reward adultery, Jim Lowell died, and Irna would have to wait to fully play out her fantasy.

Long before she found the AW bible, Lynn Liccardo saw the script for the episode that ran the day after Pat had her abortion. As she read, she said what immediately ran through her mind was, "whoever wrote this lived it." While Liccardo acknowledges there's no way to prove it "beyond a reasonable doubt," there's every reason to believe that Irna was telling the true story of her pregnancy through Pat.

It wasn't until she read the bible that Liccardo realized the extent to which Phillips was not just coming clean about how her own pregnancy ended, but creating the fully realized fantasy that would forever elude her. College junior, Pat Matthews, a younger, prettier version of Irna, is pursued by upperclassman, Tom Baxter, whose description in the AW bible bears a striking resemblance to the doctor in Dayton, who Phillips said, "left me with less than nothing." When Pat becomes pregnant, Tom urges her to terminate the pregnancy, which she does. Like Irna, the end of her pregnancy leaves Pat unable to bear children.

Then Irna's fantasy begins: In a blind rage after she confronts Tom with her sterility (and with a nod to Chekhov), Pat picks up a nearby gun, then shoots and kills him. When Pat is charged with Tom's murder, her family hires crackerjack defense attorney, John Randolph, who successfully argues temporary insanity. After her acquittal, John and Pat fall in love. And since John is older, widowed, and already has a child of his own, Pat's sterility isn't the deal breaker it was for Ralph Skilken, the two marry. Shortly after, Ed Trach said Phillips phoned PGP to say she was quitting as AW's headwriter.

According to Trach, Phillips left because she knew she wasn't doing her best work; a fact reflected in the AW's poor ratings, which were so bad rumor has it that NBC was on the verge of cancelling the show. However, Liccardo believes that the real reason was because Phillips had, at long last, finally achieved, albeit vicariously, her goal: John (Ralph Skilken) loved and married Pat (Irna) despite her sterility.

After Phillips departure, several notables served as AW's headwriter: James Lipton (of "Inside the Actors Studio" fame); Agnes Nixon; and Harding Lemay, who was, ironically, tutored by Irna Phillips on how to write for soap opera. While Lemay's disdain for and dislike of Phillips is crystal clear in "Eight Years in Another World," we'll never know what she thought of him. Since by all accounts, she was never one to suffer in silence, one can only imagine what Phillips might have said had she not died before finishing AMW.

Early in 1971, Phillips briefly became a paid story consultant for Another World. "I didn t want the burden of being a head writer which entailed the daily outlining and editing and writing of scripts but I enjoyed long-term plotting. I ended this arrangement after three months when I found that my duties would include script outlining for one of the head writers."

After a rocky start in the rating in he mid-1960's, AW would go on to be a ratings success, often posting in the top three daytime serials for the next decade.